|

|

Mona Lisa

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (8th July 2015). |

|

The Film

Mona Lisa (Neil Jordan, 1986) Mona Lisa (Neil Jordan, 1986)

After his directorial debut Angel in 1982, a gangland film set against the backdrop of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, Neil Jordan demonstrated his ability to handle diverse genres by directing the Freudian werewolf film The Company of Wolves (1984), scripted by Angela Carter, and then this film, Mona Lisa (1986), a low-key crime film set in London that shared its film noir-like sensibility with Angel. These early films demonstrate the fascination with complex sexuality and symbolism that runs throughout Jordan’s body of work, from the complex web of symbols in The Company of Wolves to the white rabbit in Mona Lisa and the apples in In Dreams (1999). After directing Mona Lisa, which along with The Company of Wolves had been very well-received critically, Jordan travelled to Hollywood and delivered two comedies that are generally considered misfires, High Spirits (1988) and the remake of We’re No Angels (1989). Following this, he returned to the UK and Ireland and directed the offbeat drama The Miracle (1991), subsequently making The Crying Game (1992), a complex picture that engages with issues of identity (national, political and gendered) that are at the core of many of Jordan’s pictures, and which remains Jordan’s most praised film. Since then Jordan has oscillated between high-profile Hollywood projects (Interview with the Vampire, 1995; Michael Collins, 1996; In Dreams) and dabbling in independent cinema (The Butcher Boy, 1997; The Good Thief, 2002), many of his films acquiring significant cult followings.  Mona Lisa opens with George (Bob Hoskins), who has spent seven years in prison, returning to his family home, only to find that his wife doesn’t anything to do with him and refuses to allow him to see his daughter. After causing a scene in the street, and making vaguely racist comments to a group of young black men who have gathered around the irate George, he is ushered away by his old friend Thomas (Robbie Coltrane), a mechanic and would-be entrepreneur: living in a mobile home that is stored in a warehouse, Thomas has gathered around him ornamental food and glowing statues of the Madonna that he intends to sell at a profit. Thomas and George share a love of paperback crime novels: Thomas kept George in a constant supply of these whilst he was in prison. They also entertain one another by coming up with increasingly outlandish thriller plots. Mona Lisa opens with George (Bob Hoskins), who has spent seven years in prison, returning to his family home, only to find that his wife doesn’t anything to do with him and refuses to allow him to see his daughter. After causing a scene in the street, and making vaguely racist comments to a group of young black men who have gathered around the irate George, he is ushered away by his old friend Thomas (Robbie Coltrane), a mechanic and would-be entrepreneur: living in a mobile home that is stored in a warehouse, Thomas has gathered around him ornamental food and glowing statues of the Madonna that he intends to sell at a profit. Thomas and George share a love of paperback crime novels: Thomas kept George in a constant supply of these whilst he was in prison. They also entertain one another by coming up with increasingly outlandish thriller plots.

Looking for his former criminal associate Denny Mortwell (Michael Caine), now a Paul Raymond-esque figure who apparently overseas an empire of sex shops and strip clubs, George is told that Denny has work for him. George is to act as chauffeur/‘ponce’ for Simone (Cathy Tyson), a high-class escort whom George describes to Thomas as ‘a tall, thin, black tart’. The relationship between Simone and George is initially tense, with both of them forced to overcome their prejudices towards the other, and Simone encouraging George to dress more appropriately for his work as her ‘ponce’. However, the pair soon grow to be more sympathetic towards one another.  Simone encourages George to cruise the King’s Cross area, driving past the prostitutes there. She is looking for her friend Cathy (Kate Hardie), a young blonde who is ‘managed’ by the American pimp Anderson (Clarke Peters). Simone, who used to work the same area as Cathy and was also ‘managed’ by Anderson, wants to rescue her friend from the misery of life as a street-walker and drug addict. George, who sees in the young women outside King’s Cross a dark mirror image of his estranged teenage daughter, is all too willing to help Simone. However, Mortwell, who is in business with Anderson and uses his ‘stable’ of prostitutes to provide ammunition for blackmailing their clients, has other plans and asks George to spy on Simone and report back to him. Believing that his relationship with Simone has romantic potential, the lonely George spurs Mortwell and continues to help Simone track down Cathy. Simone encourages George to cruise the King’s Cross area, driving past the prostitutes there. She is looking for her friend Cathy (Kate Hardie), a young blonde who is ‘managed’ by the American pimp Anderson (Clarke Peters). Simone, who used to work the same area as Cathy and was also ‘managed’ by Anderson, wants to rescue her friend from the misery of life as a street-walker and drug addict. George, who sees in the young women outside King’s Cross a dark mirror image of his estranged teenage daughter, is all too willing to help Simone. However, Mortwell, who is in business with Anderson and uses his ‘stable’ of prostitutes to provide ammunition for blackmailing their clients, has other plans and asks George to spy on Simone and report back to him. Believing that his relationship with Simone has romantic potential, the lonely George spurs Mortwell and continues to help Simone track down Cathy.

Sean Connery was reputedly in line to play George, though Hoskins inhabits the role so strongly it’s difficult to imagine what Connery might have done with it: as it stands, the picture makes a fascinating companion piece to The Long Good Friday (John Mackenzie, 1980), also starring Hoskins, in terms of its focus on the changing face of London. (Arrow have released the two films in quick succession, and have also issued a boxed set containing both pictures and an additional disc which includes John Mackenzie’s 1977 educational short ‘Apaches’. You can see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of The Long Good Friday here.) To some extent, Jordan’s characteristically poetic approach to his material would seem to be at odds with the social realism associated with the work of scriptwriter David Leland, whose Tales Out of School series of television movies for Channel 4 (comprising Made in Britain, 1982; Flying Into the Wind, 1983; Birth of a Nation, 1983; and R.H.I.N.O., 1983) functioned as ‘state of the nation’ television and showed a preoccupation with realist modes of narrative. However, the two approaches dovetail wonderfully, with the effect that some of the more symbolic elements within the script (the white rabbit that George presents to Mortwell, which could be said to symbolise a number of things, and which appears bizarrely at the climax) are integrated organically into the narrative rather than jarring with it. (The closing sequence, which adds a layer of complexity to the story and retrospectively leads the viewer to question the reliability and ‘realism’ of George’s guiding point-of-view/narrative voice, helps to ensure that the symbolism ‘fits’ with the material.)  It has been suggested that British crime and gangster films of the 1980s showed an increasing stylisation and fascination with concerns and techniques which had traditionally been the realm of ‘art’ cinemas (see Hill, 1999: 160). In John Hill’s words, the films ‘display a determination to be more than “just thrillers” by combining gangster story-lines with a degree of social and political commentary’ (ibid.). The environments in which the films’ narratives take place became increasing abstract and symbolic, as can be seen in pictures such as The Hit (Stephen Frears, 1984) and Empire State (Ron Peck, 1988). Like The Long Good Friday before it (and the later Empire State), Mona Lisa reflects on the state of London and ‘the clash between the old and new London’ (ibid.: 166). There’s visual juxtaposition of the lurid porno shops of Soho and the red light district near King’s Cross with the luxury of the posh hotels in which Simone entertains her clients, and between the dog-like loyalty of the ‘old-school’ crook George and the new Thatcherite principles of Mortwell, who whilst George has been in prison demonstrated himself to be something of an entrepreneur, building an empire for himself that is predicated on the exploitation of sexuality. It has been suggested that British crime and gangster films of the 1980s showed an increasing stylisation and fascination with concerns and techniques which had traditionally been the realm of ‘art’ cinemas (see Hill, 1999: 160). In John Hill’s words, the films ‘display a determination to be more than “just thrillers” by combining gangster story-lines with a degree of social and political commentary’ (ibid.). The environments in which the films’ narratives take place became increasing abstract and symbolic, as can be seen in pictures such as The Hit (Stephen Frears, 1984) and Empire State (Ron Peck, 1988). Like The Long Good Friday before it (and the later Empire State), Mona Lisa reflects on the state of London and ‘the clash between the old and new London’ (ibid.: 166). There’s visual juxtaposition of the lurid porno shops of Soho and the red light district near King’s Cross with the luxury of the posh hotels in which Simone entertains her clients, and between the dog-like loyalty of the ‘old-school’ crook George and the new Thatcherite principles of Mortwell, who whilst George has been in prison demonstrated himself to be something of an entrepreneur, building an empire for himself that is predicated on the exploitation of sexuality.

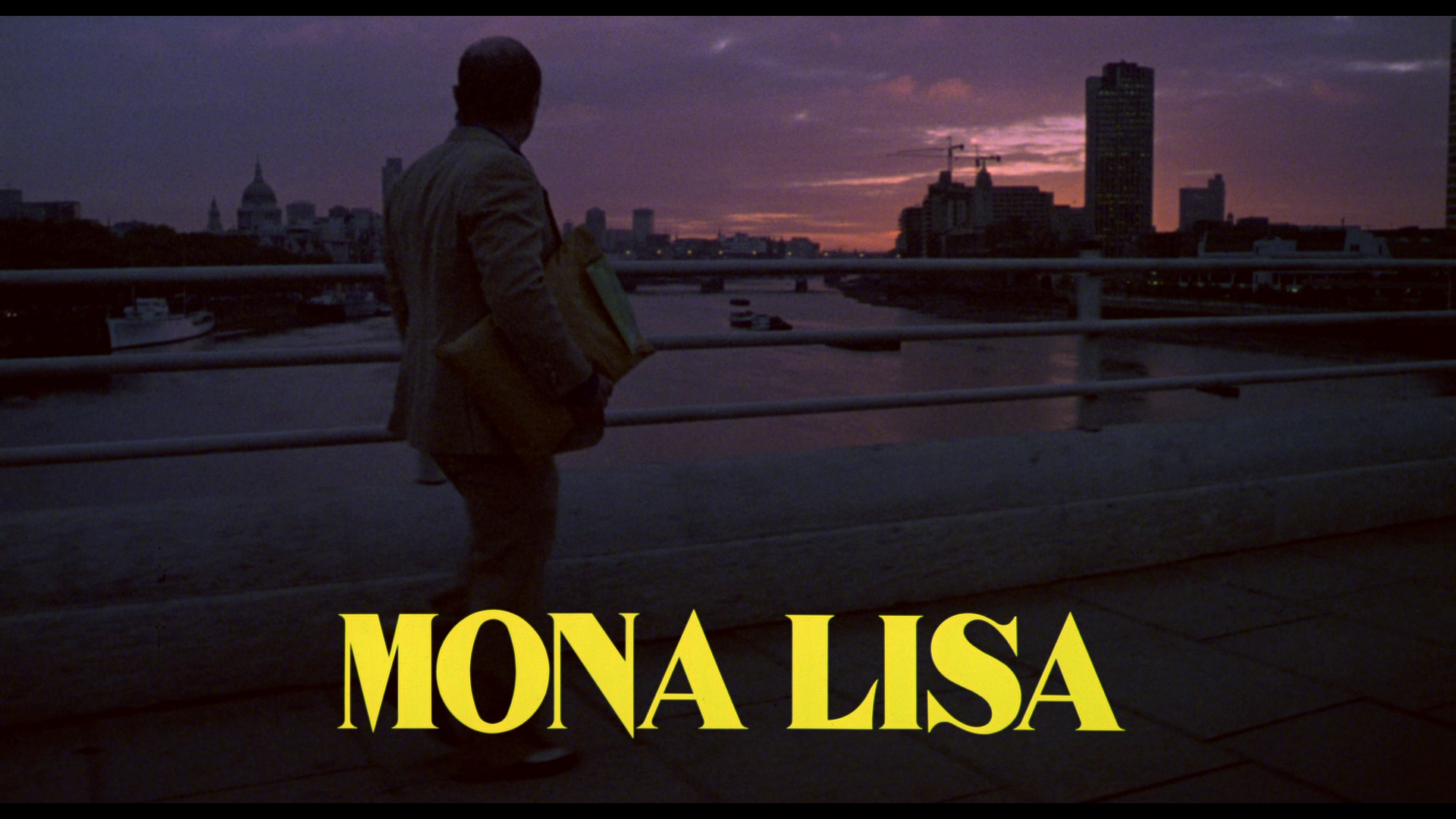

London in this film is a cold, alienating environment. We first see George walking across a bridge after being released from prison, presumably having taken the fall for Mortwell; he clutches a paper bag that contains what we assume to be his earthly belongings. He returns home for the first time in seven years, finding his wife furious at him to the point of refusing to allow him to see his daughter. George and his wife argue on the doorstep, George spilling rubbish all over the street. A group of young black men, George’s family’s neighbours, gather round and ask George if he’s going to tidy up the mess he has made on the pavement. George responds angrily but is ushered away by Thomas, who arrives on the scene just in time to save George from getting involved in a fight. Referring to the ethnicity of the young men who challenged him, George asks Thomas, ‘So where’d they all come from?’ ‘They live here’, Thomas replies. ‘Since when?’, George asks. ‘Since you went inside’, is Thomas’ reply. With this sequence, Jordan establishes the prejudices that exist within George which will be foregrounded in his early meetings with Simone.  The sequence parallels a similar moment in The Long Good Friday, in which Bob Hoskins, as gangster Harold Shand, pays a visit to Brixton to interrogate Errol, a ‘grass’ for the police, about who has been attacking Shand’s ‘corporation’. Whilst in Brixton, Shand demonstrates thinly-veiled contempt for the black Britons who live there, treating them ‘with a mixture of contempt and paternalism’ (Walsh, 2000: 292). Upon his arrival in Brixton, Shand talks to a young black man and reflects on the very different ethnic makeup of the area compared with how it used to be when Shand was a youth, asserting, ‘Used to be a nice street this. Decent families. No scum’. Arriving in Erroll’s flat for ‘verbals’, Shand picks up a hypodermic needle, passing mealy-mouthed judgement on Erroll’s apparent drug habit: ‘Filth’, Shand asserts, ‘Is there no decency in this disgusting world?’ Shand, it has been argued, is a ‘gangster proletarian’ who ‘takes for granted his supremacy over the members of immigrant communities’ (ibid.: 292). The sequence parallels a similar moment in The Long Good Friday, in which Bob Hoskins, as gangster Harold Shand, pays a visit to Brixton to interrogate Errol, a ‘grass’ for the police, about who has been attacking Shand’s ‘corporation’. Whilst in Brixton, Shand demonstrates thinly-veiled contempt for the black Britons who live there, treating them ‘with a mixture of contempt and paternalism’ (Walsh, 2000: 292). Upon his arrival in Brixton, Shand talks to a young black man and reflects on the very different ethnic makeup of the area compared with how it used to be when Shand was a youth, asserting, ‘Used to be a nice street this. Decent families. No scum’. Arriving in Erroll’s flat for ‘verbals’, Shand picks up a hypodermic needle, passing mealy-mouthed judgement on Erroll’s apparent drug habit: ‘Filth’, Shand asserts, ‘Is there no decency in this disgusting world?’ Shand, it has been argued, is a ‘gangster proletarian’ who ‘takes for granted his supremacy over the members of immigrant communities’ (ibid.: 292).

In terms of the geography of London, Simone repeatedly goads George into returning to the red light district surrounding King’s Cross, its streetwalkers and dingy lighting placed in stark juxtaposition with the plush surroundings of the upmarket hotels in which Simone plies her trade. Andrew Spicer has suggested that the film presents the King’s Cross area as ‘lit to resemble a hell’s mouth. Jordan wanted these scenes to have a Dantean quality and for the film’s look to become progressively more stylised and phantasmagorical’ (Spicer, 2007: 122). Later, in the service of Simone’s quest to ‘rescue’ Cathy, George wanders in and out of the seedy strip clubs and porno shops in Soho.  With its predominantly night-time setting, its seemingly doomed protagonist who becomes involved with a femme fatale, and its focus on the seedy underbelly of the city, Mona Lisa has a strong flavour of American films noir. With its narrative trajectory involving George, essentially hired as a chauffeur for Simone, driving around London, visiting sex shops in his quest (initiated by Simone) to save Cathy and the constant narrative push towards an inevitably bloody climax, Mona Lisa echoes the structure and thematic concerns of Martin Scorsese’s neo-noir Taxi Driver (1976). The close-ups of George’s eyes, reflected in the rear view mirror of his Jaguar, are a part of the iconography that both films share. (In fact, I remember my first viewing of Jordan’s film, on VHS in the early 1990s, leaving me with the misguided negative impression that Mona Lisa was simply a British reworking of Scorsese’s film; subsequent viewings have reversed that initial impression, foregrounding for me the richness of Jordan’s mise-en-scène, the depth of the performances of many of the principal actors, and the sensitive exploration of the changing cultural landscape of London.) As an ‘answer’ to Taxi Driver, Mona Lisa is matched by Ki-Duk Kim’s thematically similar, and equally captivating, Bad Guy (2001). With its predominantly night-time setting, its seemingly doomed protagonist who becomes involved with a femme fatale, and its focus on the seedy underbelly of the city, Mona Lisa has a strong flavour of American films noir. With its narrative trajectory involving George, essentially hired as a chauffeur for Simone, driving around London, visiting sex shops in his quest (initiated by Simone) to save Cathy and the constant narrative push towards an inevitably bloody climax, Mona Lisa echoes the structure and thematic concerns of Martin Scorsese’s neo-noir Taxi Driver (1976). The close-ups of George’s eyes, reflected in the rear view mirror of his Jaguar, are a part of the iconography that both films share. (In fact, I remember my first viewing of Jordan’s film, on VHS in the early 1990s, leaving me with the misguided negative impression that Mona Lisa was simply a British reworking of Scorsese’s film; subsequent viewings have reversed that initial impression, foregrounding for me the richness of Jordan’s mise-en-scène, the depth of the performances of many of the principal actors, and the sensitive exploration of the changing cultural landscape of London.) As an ‘answer’ to Taxi Driver, Mona Lisa is matched by Ki-Duk Kim’s thematically similar, and equally captivating, Bad Guy (2001).

Fidelma Farley has suggested that, shaped by American films noir, Jordan’s films – and in particular Mona Lisa – feature largely passive protagonists who fail to comprehend the world around them or their relationship with it, thus allowing themselves to become the ‘patsy’ (Farley, 2002: 190). (John Dahl’s first few American neo-noir pictures, made roughly contemporaneously with Mona Lisa and The Crying Game, feature a similar focus on the ‘patsy’ or ‘fall guy’ as an emblem of their roots in classic film noir: for example, the way in which Mike Swale allows Bridget to manipulate him into committing the murder of her husband in The Last Seduction, 1994; or how private investigator Jack Andrews falls prey to the machinations of femme fatale Fay in Kill Me Again, 1989.) In Mona Lisa, George is out of step, displaying the attitudes of the 1970s (and the car to match). He struggles with new technology: after taking on the job that he is offered by Mortwell, he is presented with a bleeper but fails to comprehend how it works (‘I can’t understand it. How’s that little thing supposed to go bleep wherever I am?’, he asks Thomas disbelievingly). George is inarticulate, chauvinistic and potentially racist. Women are unknowable to him. After the argument with his wife, George asks his friend Thomas, ‘Why does she hate me, Thomas?’ Thomas replies: ‘She doesn’t [….] You never can tell with women, George: they’re different. They wear skirts and like to powder their noses, and when they go to heaven they get wings’. ‘Like angels?’, George asks. ‘Aye, like Angels’, Thomas says. ‘But angels are men, Thomas’, George protests, ‘It’s true: angels are men’.  Throughout the rest of the film, like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, George perceives himself to be the ‘white knight’, or angel, who rescues Simone and Cathy. However, he is taken for a patsy by Simone, who keeps George unaware that she and Cathy are in fact lesbian lovers. Simone strings George along to achieve her aim. George’s perspective guides the narrative, and as a consequence the audience don’t realise that he is being used as a patsy until the final scenes: we’ve been conditioned by Hollywood films to expect ‘odd couple’ romances, so for much of the film’s running time we may share George’s hope that his relationship with Simone will become infused with romance. Throughout the rest of the film, like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, George perceives himself to be the ‘white knight’, or angel, who rescues Simone and Cathy. However, he is taken for a patsy by Simone, who keeps George unaware that she and Cathy are in fact lesbian lovers. Simone strings George along to achieve her aim. George’s perspective guides the narrative, and as a consequence the audience don’t realise that he is being used as a patsy until the final scenes: we’ve been conditioned by Hollywood films to expect ‘odd couple’ romances, so for much of the film’s running time we may share George’s hope that his relationship with Simone will become infused with romance.

In exploring George’s interactions with Simone, Jordan alludes to Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). In that film, John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson (James Stewart) becomes obsessed with high society heiress Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak); but after Madeleine apparently commits suicide, Scottie transplants that obsession onto lowly shop worker Judy Barton (also played by Kim Novak), going to great lengths to ‘dress’ Judy as Madeleine – unaware that Madeleine really was Judy, who was masquerading as Madeleine Elster as part of a murder plot. To achieve Judy’s transformation into the object of his desire, Scottie buys Judy clothes dictates to a shop assistant the precise details of how he wishes Judy to dress. Jordan replays this relationship in Mona Lisa but reverses the gender roles. After the uncouth George arrives in a plush hotel to collect her for the first time, Simone gives George some money and tells him to buy some new clothes. ‘I’m not having you paying me’, George protests. ‘Why not?’, Simone asks. ‘You don’t even like me’, George tells her. The next evening, George arrives to collect Simone whilst wearing a garish Hawaiian shirt and a tacky caramel-coloured leather jacked. ‘You don’t like ‘em?’, George asks, referring to his clothes. ‘Do you?’, Simone queries. ‘Well, I bought ‘em, didn’t I?’, is George’s response. To this, Simone tells him, ‘You’re as much cover as a pair of fishnet tights. I may as well be wearing a sign around my neck. All you’re missing is the gold medallion’. In response to this, George opens the neck of his shirt slightly and shows Simone the gold medallion he is wearing (‘You don’t like them either?’, he asks). ‘See, I’m cheap. I can’t help it. God made me that way’, George asserts. ‘Being cheap is one thing. Looking cheap is another. That really takes talent’, Simone tells him. ‘Some women are whores’, George philosophises, ‘Some whores are black. You take what you’re given, don’tcha?’  Later, Simone takes George to an upmarket men’s clothes shop. ‘What do you want to wear men’s clothes for?’, George asks her, believing that they are there to expand Simone’s wardrobe. ‘I don’t. It’s for you’, she tells him. ‘For me? You can’t dress me’, he protests. However, he soon relents, allowing Simone to remake him in a similar way to which Scottie remakes Judy in Vertigo. However, in the next sequence George reveals that though his outer appearance may be different, his ‘out of place’ behaviour is still present: waiting for Simone at the posh hotel in his new clothes, George asks a waiter for ‘a pot of tea’. ‘Earl Grey or lapsang souchong?’, the waiter asks. ‘No, tea’, George clarifies, unaware of the irony. Later, Simone takes George to an upmarket men’s clothes shop. ‘What do you want to wear men’s clothes for?’, George asks her, believing that they are there to expand Simone’s wardrobe. ‘I don’t. It’s for you’, she tells him. ‘For me? You can’t dress me’, he protests. However, he soon relents, allowing Simone to remake him in a similar way to which Scottie remakes Judy in Vertigo. However, in the next sequence George reveals that though his outer appearance may be different, his ‘out of place’ behaviour is still present: waiting for Simone at the posh hotel in his new clothes, George asks a waiter for ‘a pot of tea’. ‘Earl Grey or lapsang souchong?’, the waiter asks. ‘No, tea’, George clarifies, unaware of the irony.

Simone is an enigma to George. The film’s title, Mona Lisa, alludes to Simone: she is a mystery onto which George paints his hopes and desires. The use of Nat King Cole’s music within the film, especially the songs ‘Mona Lisa’ and ‘When I Fall in Love’ (both of which the film associates with George, frequently playing in his car as he waits for Simone or drives her to her next destination), foreground George’s romantic dreams and delusions. Neil Jordan has suggested that he felt ‘[t]here was too much music’ in the final version of the film and wanted to ‘take a lot of it off’, but Handmade Films felt that the film’s ‘subject matter was kind of repellent and it needed all this music’ (Jordan, quoted in Falsetto, 1997: 14). However, the Nat King Cole songs, ‘songs of male isolation and romantic confusion’, are an integral part of the film (Jordan, quoted in ibid.). (Jordan’s later The Crying Game featured a similarly pensive use of popular music – in the case of that film, Geoff Stephens’ song of the same title, Percy Sledge’s ‘When a Man Loves a Woman’ and Tammy Wynett and Billy Sherrill’s ‘Stand By Your Man’.) George’s only solace is his time spent in the company of his friend Thomas, played with genial warmth by Robbie Coltrane, who kept the incarcerated George occupied by feeding him a steady diet of pulpy paperback crime novels. George and Thomas spend time together, George staying in Thomas’ mobile home. Gradually, George builds a relationship with his estranged daughter. These are the two characters who form George’s family, and it’s fitting that the film ends on a shot of the three of them, arm-in-arm.  The film is uncut and runs for 103:51 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Arrow’s presentation of the film is in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Based on a new 2k scan that was graded under the supervision of Neil Jordan and the film’s Director of Photography, Roger Pratt, the 1080p presentation (using the AVC codec) demonstrates excellent, balanced contrast levels, which are evidenced within the film’s many night-time sequences: for example, the opening shot of the solitary George, carrying his possessions in a brown paper bag, walking through London as the night turns to dawn. (These more refined contrast levels, with much improved shadow detail, are arguably the biggest difference between this new release and the film’s previous DVD releases.) Taking up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Arrow’s presentation of the film is in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Based on a new 2k scan that was graded under the supervision of Neil Jordan and the film’s Director of Photography, Roger Pratt, the 1080p presentation (using the AVC codec) demonstrates excellent, balanced contrast levels, which are evidenced within the film’s many night-time sequences: for example, the opening shot of the solitary George, carrying his possessions in a brown paper bag, walking through London as the night turns to dawn. (These more refined contrast levels, with much improved shadow detail, are arguably the biggest difference between this new release and the film’s previous DVD releases.)

The level of detail is very strong and there’s a superb sense of depth to the image, enabled by the production’s use of mostly short focal lengths (which have shorter hyperfocal distances), presumably because so much of the film takes place in confined spaces (in George’s Jaguar, in narrow corridors, in porno shops). This results in many shots staged in depth, which are communicated very well in this new scan. Fine detail (for example, in facial close-ups) is excellent, and the superb encode ensures that the film has the texture of 35mm film, with a natural and organic grain structure present throughout. NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is rich with very good range, as evidenced in the range demonstrated in the use of Nat King Cole’s ‘Mona Lisa’ over the film’s opening credits. It’s a clean, clear track. Optional English HoH subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Neil Jordan and Bob Hoskins. This is the same audio commentary that was first used on Criterion’s DVD release of the film in the US. It’s an interesting track in which Jordan engages in detail with the film’s themes, and Hoskins reflects particularly on his performance as George. - New interviews with: -- Neil Jordan (19:58). Jordan talks about the development of Mona Lisa, his relationship with David Leland, and the production of the film – paying particular attention to some of the work of the principal cast. -- Stephen Woolley (13:37). Woolley reflects on his involvement as the film’s producer and the development of the picture. -- David Leland (19:01). Leland examines his script for the film, revealing that during the writing stage he believed Michael Caine would be playing the lead role. He also discusses some of the changes that were made to his script. - The film’s trailer (2:32).

Overall

Mona Lisa is a stark, unsentimental film that owes much to American films noir of the 1950s. There are echoes here of Paul Schrader’s scripts for Taxi Driver and Hardcore (Paul Schrader, 1979), in terms of George’s desire to ‘rescue’ a ‘fallen’ woman and his growing fascination with the seedy underbelly of the city: its strip clubs and porno shops. (The film also makes an interesting companion piece to Ki-Duk Kim’s Bad Guy.) However, Jordan makes this material his own through an examination of London and the changing ‘texture’ of the city that to some extent allies Mona Lisa with The Long Good Friday. Mona Lisa is a stark, unsentimental film that owes much to American films noir of the 1950s. There are echoes here of Paul Schrader’s scripts for Taxi Driver and Hardcore (Paul Schrader, 1979), in terms of George’s desire to ‘rescue’ a ‘fallen’ woman and his growing fascination with the seedy underbelly of the city: its strip clubs and porno shops. (The film also makes an interesting companion piece to Ki-Duk Kim’s Bad Guy.) However, Jordan makes this material his own through an examination of London and the changing ‘texture’ of the city that to some extent allies Mona Lisa with The Long Good Friday.

As with their recent Blu-ray release of The Long Good Friday, Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Mona Lisa shows a highly commendable level of care and attention given to the film’s presentation, which easily eclipses the film’s previous home video releases. Coupled with the superb presentation of the main feature, some strong contextual material ensures that this release comes with a very strong recommendation.  References: Falsetto, Mario, 1997: ‘Conversation with Neil Jordan’. In: Zucker, Carole (ed), 2013: Neil Jordan: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 3-30 Farley, Fidelma, 2002: ‘Neil Jordan’. In: Tasker, Yvonne (ed), 2002: Fifty Contemporary Filmmakers. London: Routledge: 186-94 Hill, John, 1999: ‘Allegorising the nation: British gangster films of the 1980s’. In: Chibnall, Steve & Murphy, Robert (eds), 1999: British Crime Cinema. London: Routledge: 160-71 Spicer, Andrew, 2007: European Film Noir. Manchester University Press Walsh, Michael, 2000: ‘Thinking the unthinkable: coming to terms with Northern Ireland in the 1980s and 1990s’. In: Ashby, Justine & Higson, Andrew (eds), 2000: British Cinema, Past and Present. London: Routledge: 288-98

|

|||||

|