|

|

Valentino (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - British Film Institute Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th March 2016). |

|

The Film

Valentino (Ken Russell, 1977) Valentino (Ken Russell, 1977)

Opening with Rudolph Valentino (Rudolf Nureyev) in his coffin, his adoring/rabid fans outside the salon where his body is on display, Ken Russell’s Valentino (1977) adopts a flashback structure similar to that of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) or Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946), with various characters (all women) associated with Valentino gathering in the funeral parlour and being interviewed by members of the press. These include Bianca De Saulles (Emily Bolton), who first encountered Valentino whilst he was working as a taxi dancer in a New York establishment owned by Billie Streeter (Linda Thorson). When Streeter fires Valentino, he flees with Streeter, whose husband Jack (Robin Clarke) breaks into Valentino’s apartment and attacks him. Streeter, fearing that her husband’s thugs will abduct her child, shoots Jack. The controversy surrounding these events precipitates Valentino’s move to California. Bianca’s reflections on Valentino’s life are followed by those of June Mathis (Felicity Kendal), a Hollywood executive whose recollections of Valentino begin with her first encounter with him: at Baron Long’s (Anton Diffring) establishment, where June was impressed with Valentino’s lack of fear in mocking the loudmouthed bully Fatty Arbuckle (William Hootkins). June’s memories of Valentino also encompass his marriage to Jean Acker (Carol Kane), one of Arbuckle’s associates and an actress whose lavish lifestyle pushes Valentino towards considering acting in films as a career; June aids Valentino in achieving this goal.  Next to reflect on her relationship with Valentino is Alla Nazimova (Leslie Caron), who after making a grand, attention-grabbing entrance recalls to the newspapermen her first meeting with Valentino on the set of Rex Ingram’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921). Nazimova’s recollections are followed by those of Natacha Rambova (Michelle Phillips), Nazimova’s former lover who seduced Valentino on the set of George Melford’s The Sheik (1921), gradually drawing Valentino into her spiritualist philosophy and practices. When Rambova and Valentino decide to marry in Mexico, to avoid the ‘problem’ of Valentino’s still-binding marriage to Jean Acker, upon returning to the US they are thrown into jail for bigamy. Acker manages to secure her release, but Valentino is abandoned by studio executive Jesse Lasky (Huntz Hall), for whom Valentino’s imprisonment is good publicity, and as a consequence Valentino suffers sexual humiliation at the hands of a cruel policeman (Bill McKinney) and the other inmates – especially Willie (Dudley Sutton). Next to reflect on her relationship with Valentino is Alla Nazimova (Leslie Caron), who after making a grand, attention-grabbing entrance recalls to the newspapermen her first meeting with Valentino on the set of Rex Ingram’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921). Nazimova’s recollections are followed by those of Natacha Rambova (Michelle Phillips), Nazimova’s former lover who seduced Valentino on the set of George Melford’s The Sheik (1921), gradually drawing Valentino into her spiritualist philosophy and practices. When Rambova and Valentino decide to marry in Mexico, to avoid the ‘problem’ of Valentino’s still-binding marriage to Jean Acker, upon returning to the US they are thrown into jail for bigamy. Acker manages to secure her release, but Valentino is abandoned by studio executive Jesse Lasky (Huntz Hall), for whom Valentino’s imprisonment is good publicity, and as a consequence Valentino suffers sexual humiliation at the hands of a cruel policeman (Bill McKinney) and the other inmates – especially Willie (Dudley Sutton).

Upon release from prison, Valentino finds himself drawn into a conflict with Lasky that is engineered by Natacha, who withdraws Valentino’s labour from the film studio. Out of work, Valentino is approached by private businessman George Ullman (Seymour Cassel), who proposes that Valentino and Natacha should attach themselves to his traveling dance troupe. Natacha refuses to take part in the vaudeville show that Ullman is proposing, but Valentino agrees. After returning once more to the present, the film journeys back to the past to depict the mocking of Valentino’s sexuality by the press, which culminates in Valentino holding a press conference in which he challenges the author of a particularly malicious article to a boxing match. The writer isn’t there; but Rory O’Neil (Peter Vaughan), the former heavyweight champion of the US navy, is, and he accepts the challenge in the stead of the writer of the article. Valentino and O’Neil meet in the boxing ring, in the events that lead directly up to Valentino’s lonely death.  Russell’s film was based on Brad Steiger & Chaw Mank’s biography of Valentino, Valentino: An Intimate and Shocking Expose. Originally, Russell planned to make a biopic of Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky and considered casting Nureyev in the lead role; but this project evolved into Valentino, with Nureyev originally to play Nijinsky, who appears as a character very briefly in the finished picture, dancing with Valentino at Miss Billie’s club. However, Nureyev was eventually given the title role of Valentino himself. Nureyev plays Valentino as a good-natured, gentle soul – slightly effeminate and ambiguous in terms of his sexuality, which was a major sticking point for many of the film’s critics. Russell’s film was based on Brad Steiger & Chaw Mank’s biography of Valentino, Valentino: An Intimate and Shocking Expose. Originally, Russell planned to make a biopic of Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky and considered casting Nureyev in the lead role; but this project evolved into Valentino, with Nureyev originally to play Nijinsky, who appears as a character very briefly in the finished picture, dancing with Valentino at Miss Billie’s club. However, Nureyev was eventually given the title role of Valentino himself. Nureyev plays Valentino as a good-natured, gentle soul – slightly effeminate and ambiguous in terms of his sexuality, which was a major sticking point for many of the film’s critics.

Like a number of Ken Russell’s films, Valentino was received poorly at the time of its release, and this initial reception has dogged the film since then. For Robert Shail, Valentino reeks of the ‘excess, self-indulgence and shallowness’ that characterise Russell’s The Music Lovers (1970) and Lisztomania (1975) (Shail, 2007: 189). Similarly, Ruth Barton suggests that the combination of the expense of the production and its commercial failure ‘nearly ended Russell’s career’ (Barton, 2014: 217). Jeanine Basinger criticises the film’s engagement with the silent era of cinema and Valentino in particular, arguing that as with the previous biopic about Valentino (Lewis Allen’s 1951 Valentino, starring Anthony Dexter), Russell’s picture offers no ‘real insight into the Valentino legend or life’ and doesn’t demonstrate any understanding of ‘silent film stardom’ (Basinger, 1999: np). Basinger also criticises Nureyev’s performance as Valentino, suggesting that it is as weak as Anthony Dexter’s performance in Lewis Allen’s picture. Jeremy G Butler has highlighted the ‘necrophilic excess’ in the treatment of Valentino’s body after his death: put on display and the object of ‘fainting spells, hysterical grief, and, to be accurate, a few suicides’ (Hansen, 1991: 290). Russell’s Valentino begins with the film’s opening titles playing out over footage of Valentino’s funeral and headlines declaring his death, whilst on the soundtrack we hear a rendition of ‘There’s a New Star in Heaven Tonight’, one of the songs written to capitalise on the passing of the actor. This titles sequence is followed by a shot of Valentino in his coffin: a close-up, filmed in monochrome. Colour slowly seeps into the image, bringing us out of the world of the newsreel footage with which the picture opens and into the diegesis of Russell’s film. The camera dollies away from the coffin, isolating it – and Valentino’s body contained within – and foregrounding the gold trim on the casket. The camera’s movement away from the coffin, diminishing it – and Valentino – within the frame foreshadows the actor’s loneliness and his difficulty in forging ‘meaningful’ connections with those around him. On the audio track can be heard the throngs of people outside banging on the door, the raucous quality of this sound in direct juxtaposition with the absolute stillness within the funeral parlour itself.  The film takes its flashback structure from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) or perhaps Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946). As in those pictures, various participants gather after the death of Valentino and, under the gaze of the press, reflect on their relationships with him. The first to gather over Valentino’s coffin are a trio of studio executives. They react to Valentino’s death not in an emotional way but in a manner which objectifies Valentino, turning him into nothing more than an index of profits for the studio itself. ‘He shoulda taken care of himself’, one of these men says, ‘A lousy appendix. Shoulda laid off the booze too. The moment he goes into the ground, our grosses go with him’. Another executive suggests an answer to this problem: ‘before they take him out of here we gotta rerelease his movies in every theatre in the country’. The film takes its flashback structure from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) or perhaps Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946). As in those pictures, various participants gather after the death of Valentino and, under the gaze of the press, reflect on their relationships with him. The first to gather over Valentino’s coffin are a trio of studio executives. They react to Valentino’s death not in an emotional way but in a manner which objectifies Valentino, turning him into nothing more than an index of profits for the studio itself. ‘He shoulda taken care of himself’, one of these men says, ‘A lousy appendix. Shoulda laid off the booze too. The moment he goes into the ground, our grosses go with him’. Another executive suggests an answer to this problem: ‘before they take him out of here we gotta rerelease his movies in every theatre in the country’.

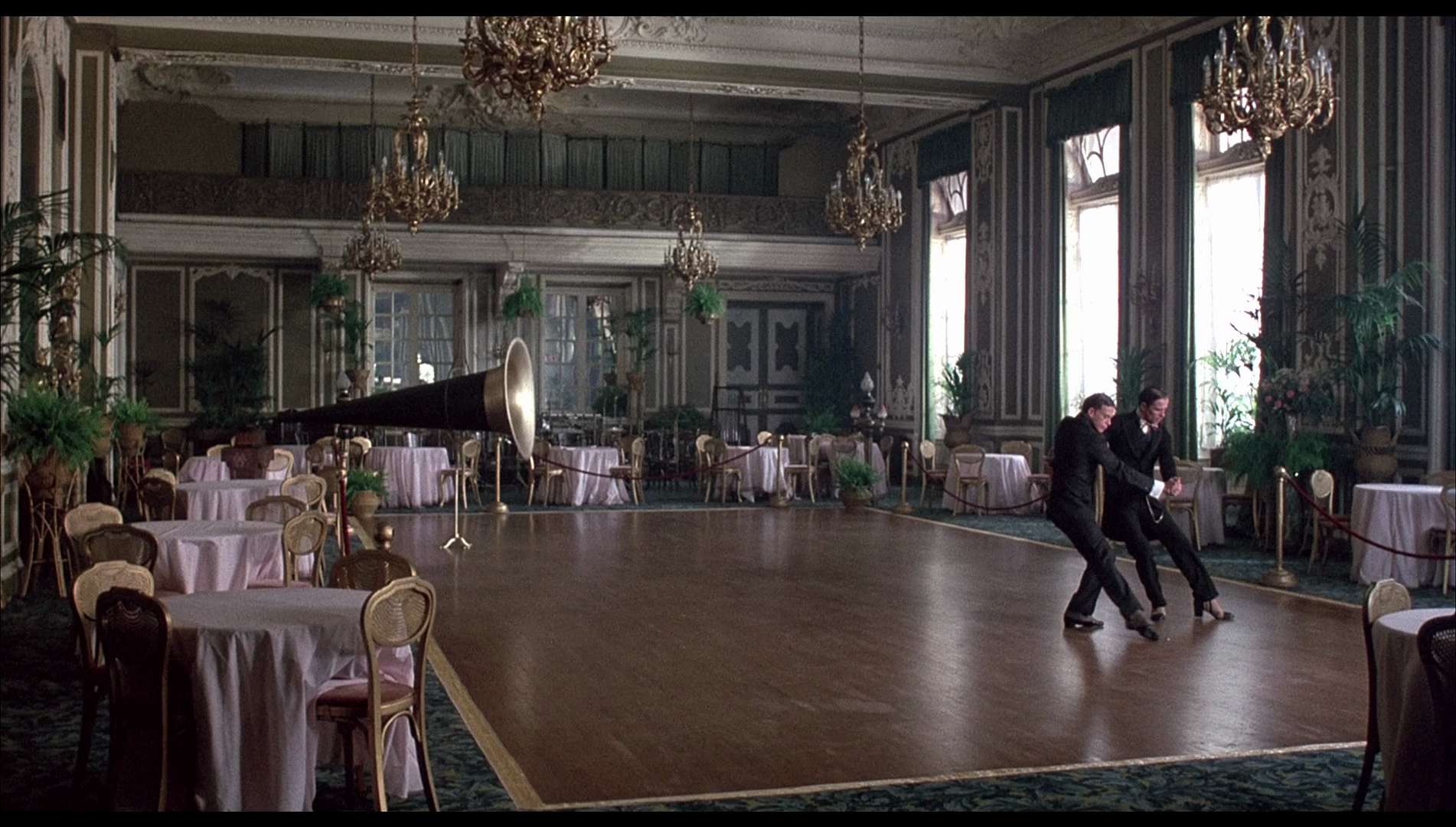

Amidst this outpouring of grief for their profits, Bianca enters the parlour. She weeps genuine tears. Not for the first time, the newspapermen refer to Valentino as ‘just a gigolo’ when he arrived in America. Bianca protests sharply, telling the journalist that Valentino ‘was not a gigolo. He was a professional dancer’. However, shortly afterwards, in Bianca’s extended flashback, despite the fact that Valentino is a taxi dancer Miss Billie suggests he should act like a gigolo: she advises him to flatter ‘some of the older broads’ because ‘they tip better’. Whilst dancing with a much older woman, Valentino does as Miss Billie suggests, responding in the affirmative when the woman with whom he is dancing begs him to ‘Come to me tonight’. Valentino’s sexuality is questioned at every turn. In the introduction of Bianca at Valentino’s coffinside, one of the newspapermen tells Bianca to ‘take a big sniff of the pansies’ whilst he snaps a photograph. ‘They’re violets’, Bianca informs him. ‘Too bad’, the newspaperman responds, ‘But from what I hear, pansies would have been more appropriate’. Bianca’s analepsis takes us to Miss Billie’s ballroom, where Bianca remembers her first encounter with Valentino, who was working as a taxi dancer for Miss Billie: in her memory, Bianca enters the large ballroom and sees Valentino dancing a tango with another man, Vaslav Nijinsky, whilst music plays from an enormous gramophone. Miss Billie enters and witnesses the scene before retiring to her office where she telephones Bianca’s husband, quipping that Valentino and Nijinsky ‘looked like [they were performing] the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy’. In response to Bianca’s husband’s query as to whether Billie believes Valentino and Bianca to have slept together, Billie tells him that ‘They don’t call him [Valentino] Saint Rudolpho for nothin’’. When Bianca’s husband confronts Bianca in Miss Billie’s club, he complains that ‘Waltzing with wops is one thing; but he’s a pansy’. ‘I’m a professional dancer’, Valentino protests. To this, Bianca’s husband responds by asserting that ‘any guy that dances with another guy is a powder puff. You got that, wop?’  Nureyev’s performance as Valentino was a sticking point for many critics at the time of the film’s release, and it’s true that Nureyev bears little physical resemblance to the real Valentino and his accent is New York Italian American-via-Castellaneta-via-Irkutsk. Through his performance, Nureyev also makes Valentino a highly flamboyant character. Despite these areas of contention, it’s certainly true that Nureyev’s Valentino displays an exuberance, a love of life that is challenged by the cruelty and prejudice that he faces. Sometimes he overcomes this and flies in the face of spite. At Miss Billie’s club, after being ridiculed by Bianca’s husband and fired from his job by Miss Bille, Valentino takes control of the situation by insisting that as he is no longer an employee, he is now a customer. Stepping on to the dance floor, he puts on an elaborate dance routine, to the applause of the other customers – who clearly love him – and the chagrin of Miss Billie and her goons. Then, in the next scene, with a handful of accomplices he bursts in on Miss Billie and Bianca’s husband, who are mid-coitus, and with a Speed Graphic camera takes their photograph in flagrante delicto, providing Bianca with grounds to divorce her husband and escape from her miserable marriage. However, this precipitate’s Bianca’s husband’s decision to send his thugs to attack Valentino and snatch Bianca’s child, resulting in Bianca’s execution of her former husband. Nureyev’s performance as Valentino was a sticking point for many critics at the time of the film’s release, and it’s true that Nureyev bears little physical resemblance to the real Valentino and his accent is New York Italian American-via-Castellaneta-via-Irkutsk. Through his performance, Nureyev also makes Valentino a highly flamboyant character. Despite these areas of contention, it’s certainly true that Nureyev’s Valentino displays an exuberance, a love of life that is challenged by the cruelty and prejudice that he faces. Sometimes he overcomes this and flies in the face of spite. At Miss Billie’s club, after being ridiculed by Bianca’s husband and fired from his job by Miss Bille, Valentino takes control of the situation by insisting that as he is no longer an employee, he is now a customer. Stepping on to the dance floor, he puts on an elaborate dance routine, to the applause of the other customers – who clearly love him – and the chagrin of Miss Billie and her goons. Then, in the next scene, with a handful of accomplices he bursts in on Miss Billie and Bianca’s husband, who are mid-coitus, and with a Speed Graphic camera takes their photograph in flagrante delicto, providing Bianca with grounds to divorce her husband and escape from her miserable marriage. However, this precipitate’s Bianca’s husband’s decision to send his thugs to attack Valentino and snatch Bianca’s child, resulting in Bianca’s execution of her former husband.

For Joseph Lanza, ‘the film’s ultimate story’ is the depiction of Valentino as ‘a good-natured and asexual, if not bisexual, dreamer who gets caught up with women who ruin him and a Hollywood dream factory that reduces him to a pretty tailor’s dummy destined to get kicked around’ (Lanza, 2007: 193). Valentino’s exuberance dominates many of the earlier sequences, but he’s repeatedly exploited and ridiculed by those around him. Following his marriage to Natacha, which takes place in Mexico to circumvent the law against bigamy, Valentino is imprisoned upon his return to California. Approached by June, Lasky refuses to help Valentino, who is now a major studio star: ‘Why spend $10,000 getting him out when we’re getting a million dollars in publicity’, Lasky reasons, ‘The more the pess knocks the boy, the bigger the box office’. Meanwhile, in his jail cell Valentino is assaulted and humiliated sexually by the other inmates (one of whom is played by Dudley Sutton), who are goaded on by the guard. The scene is disturbing and nightmarish, the guard acting as the ringleader of this cruel carnival, the amplification of spite and mania being reflected in the auditory design of the sequence – the music building up to a cacophony of sounds, in a similar manner to the orgy sequence in Russell’s earler The Devils (1971). Joseph Lanza suggests that this particular scene was disliked by everyone within the production owing to its ‘vileness and violence’ (Lanza, 2007: 193). However, this was part of the point of the sequence: the sequence ‘had to be gruesome in order to expose the rift between Valentino’s hype as a sex idol and the anti-Valentino backlash that fermented outside Hollywood’s protective bubble’ (ibid.). For his part, in the later sequences of the film Valentino expresses alienation from the world in which he has found himself, declaring his desire to be nothing more than an orange grove farmer: ‘That I should be born into such a time that a machine is invented that can turn a man who wants only to be a farmer into some kind of god’, Valentino asserts.  Elsewhere, the picture deviates from the ‘truth’ in a number of sequences: for example, Fatty Arbuckle, it’s said, was far from the loud-mouthed, grandstanding bully that he’s depicted as in the sequence set in Baron Long’s establishment, and was instead a shy, reserved man. Here, Arbuckle bursts into Baron Long’s place: he’s a manic presence, lewd and vulgar, constantly giggling. ‘What have we got here?’, he demands whilst watching Valentino dance with his admittedly drunken partner, ‘A floor show or a cattle drive?’ Arbuckle adds, ‘Hey, sister: you dance like my ass chews gum’. In response, Valentino grabs Jean Acker from Arbuckle’s table and dances with her, groping her breast and kissing her passionately. Arbuckle is incensed; Jean is aroused; June watches on, laughing at Valentino’s humiliation of Arbuckle. Elsewhere, the picture deviates from the ‘truth’ in a number of sequences: for example, Fatty Arbuckle, it’s said, was far from the loud-mouthed, grandstanding bully that he’s depicted as in the sequence set in Baron Long’s establishment, and was instead a shy, reserved man. Here, Arbuckle bursts into Baron Long’s place: he’s a manic presence, lewd and vulgar, constantly giggling. ‘What have we got here?’, he demands whilst watching Valentino dance with his admittedly drunken partner, ‘A floor show or a cattle drive?’ Arbuckle adds, ‘Hey, sister: you dance like my ass chews gum’. In response, Valentino grabs Jean Acker from Arbuckle’s table and dances with her, groping her breast and kissing her passionately. Arbuckle is incensed; Jean is aroused; June watches on, laughing at Valentino’s humiliation of Arbuckle.

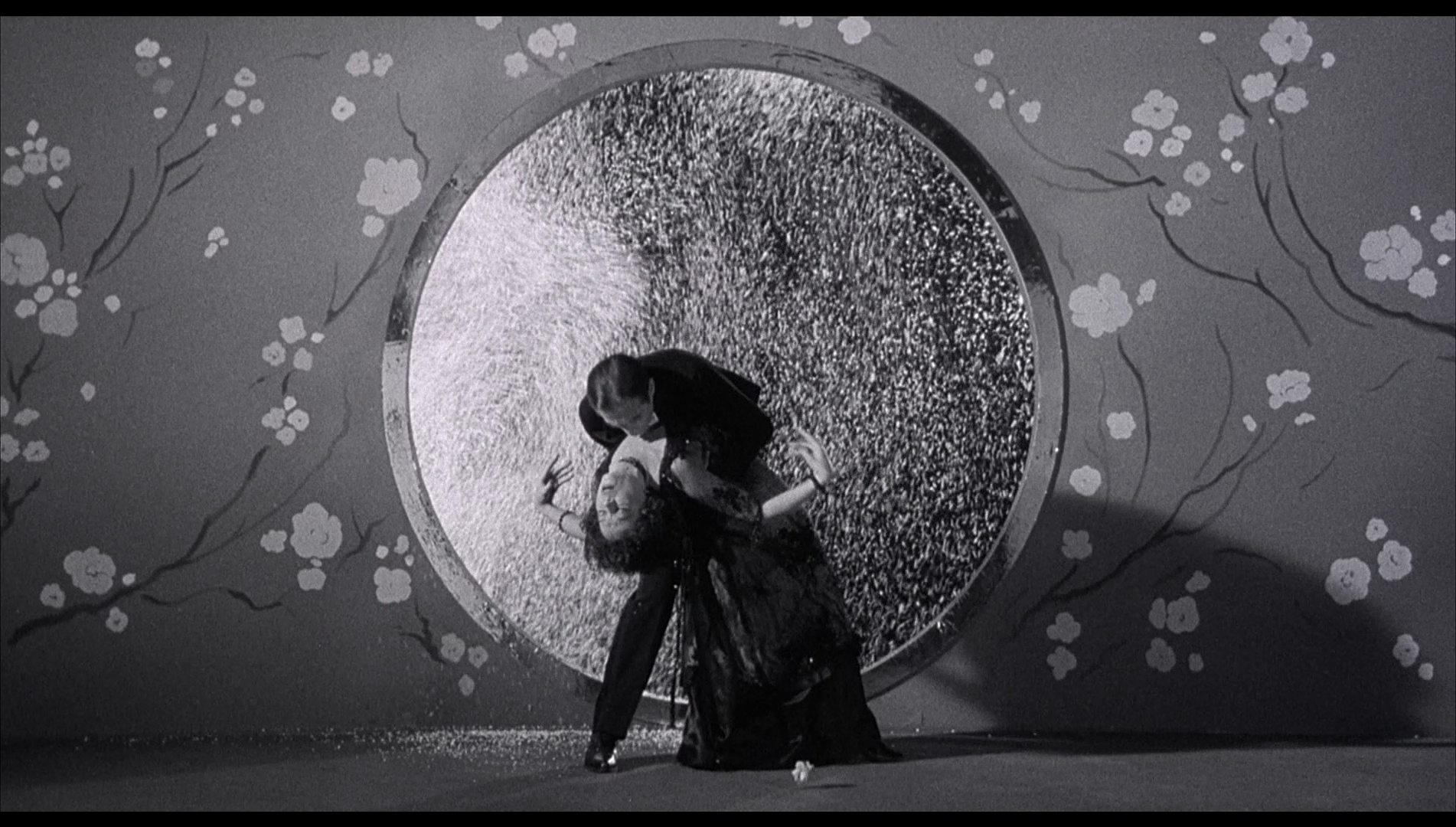

However, reviews that criticise Russell’s picture’s lack of regard for the ‘facts’ perhaps miss the point: Valentino is a picture that is concerned predominantly with the processes by which myths are made and shattered, and the role that the news media plays in this. The narrative takes place after Valentino’s death; the sequences depicting Valentino’s life are presented as the reflections of people who look back upon him romantically, through the lens of memory. The film’s structure invites suggestions that these analepses are highly subjective and may be unreliable, like the infamous ‘lying flashback’ in Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950). The labyrinthine flashbacks in Valentino allude to both Citizen Kane and, more generally, the narrative paradigms of films noir in which characters look back on their – and others – pasts with potential for error or delusion. Examples of films noir which do so include, of course, The Killers and also Laura (Otto Preminger, 1945), Detour (Edgar G Ulmer, 1944), Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) and The Locket (John Brahm, 1946). In one sequence within Valentino, the potential for error in the recollection and reportage of Valentino’s life – and death – is foregrounded when one of the newspapermen becomes involved in a minor dispute with June. The reporter tells June, ‘There’s a story going around that he [Valentino] actually died in our arms. Is that true?’ In response to this, June declares, ‘No. But if you’ve got the story, why do you want the truth?’ The exchange, at its heart, contains a similar message to the famous dictum from John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962): ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend’. In fact, the film foregrounds the artifice and performative aspects of cinema itself. ‘All you need in movies is to look sincere’, Jean tells Valentino after he has seduced her, before adding ‘Let me tell you, there’s nothing sincere in this town’. She adds that in silent pictures, as ‘nobody can hear what you say’ when her characters are supposed to be talking, instead of saying her lines ‘I just make up a load of cuss words instead’. Later, in Alla Nazimova’s flashback to her first encounter with Valentino on the set of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Nazimova takes in the carefully-constructed mise-en-scčne on the set and declares ‘What daring! What symbolism!’ Natacha bursts Nazimova’s bubble by responding, simply, ‘What horseshit!’

Video

As in a number of Russell’s other films, the director had significant input into the photography of the film, allowing his director of photography (in this case, Peter Suschitzky, ‘only [a] tiny area of autonomy’ within the lighting of the picture, ‘and even that was rigorously policed’ by Russell (Harper & Smith, 2012: 156). Certainly, it’s a very stylised film, both in terms of mise-en-scčne (with elaborate Art Deco sets) and photography. As in a number of Russell’s other films, the director had significant input into the photography of the film, allowing his director of photography (in this case, Peter Suschitzky, ‘only [a] tiny area of autonomy’ within the lighting of the picture, ‘and even that was rigorously policed’ by Russell (Harper & Smith, 2012: 156). Certainly, it’s a very stylised film, both in terms of mise-en-scčne (with elaborate Art Deco sets) and photography.

Taking up approximately 34Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, this 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. With a running time of 127:38 mins, the film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The image is beautifully detailed, and displays finely-balanced contrast. Colour reproduction is very impressive: for example, in the shots of Valentino in his coffin, the palour of his face offset by the red lipstick and framed by the silk lining of the coffin itself. A strong encode to disc ensures that the film retains the structure of 35mm film, offering what is a very pleasing viewing experience.

Audio

The disc offers the option of an LPCM 1.0 mono mix and an LPCM 2.0 stereo mix, both accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The two mixes are clean and clear; the former obviously lacks the separation of the latter, but other than that both offer an equally good experience. The disc offers the option of an LPCM 1.0 mono mix and an LPCM 2.0 stereo mix, both accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The two mixes are clean and clear; the former obviously lacks the separation of the latter, but other than that both offer an equally good experience.

Extras

The disc includes:  - an audio commentary with critic Tim Lucas. Lucas delivers one of his typically well-researched and carefully-scripted commentary tracks, which begins with a discussion of how the picture ‘may look like a Hollywood biopic from afar’ but offers ‘much more than that’. It’s a very good track, packed with information and insight, that is more than worthy of a viewer’s time. - an audio commentary with critic Tim Lucas. Lucas delivers one of his typically well-researched and carefully-scripted commentary tracks, which begins with a discussion of how the picture ‘may look like a Hollywood biopic from afar’ but offers ‘much more than that’. It’s a very good track, packed with information and insight, that is more than worthy of a viewer’s time.

- Tonight: Rudolf Nureyev on Valentino and Ken Russell (9:33). In this interview, Nureyev discusses his acting role in the picture and the experience of working with Ken Russell. He talks about the nudity in the picture, suggesting that his nude scene with Michelle Phillips ‘is more like a dance’ than anything else, and was closely choreographed. In response to the question of how close the picture is to ‘the real Valentino’, Nureyev suggests that Russell had ‘a predisposition to unpluck the feathers from the bird, to unmake the idols’. - Dudley Sutton Remembers Ken Russell and Filming Valentino (21:48). In this new interview, Sutton reflects on his first meetings with Russell and his casting in The Devils. Sutton suggests that when making The Devils ‘what appalled me was the narrow-mindedness and the sexual insanity of the guys in the film business’. He discusses the process by which the press coverage of The Devils turned the picture, in many people’s minds, into ‘a dirty film’. ‘The moment you get to Rome, Ken Russell’s a hero’, Sutton suggests, ‘Here, they wouldn’t give him the time of day’. Russell approached Sutton with the role of ‘Willy the Wanker’ in Valentino. Sutton also reflects on Nureyev and the experience of acting with him. He discusses Russell’s tendency to cast non-actors in his films, and Sutton suggests that ‘often non-actors respect you’. Sutton also talks about Russell’s tendency to cut no corners in the designing of the sets of his films: ‘I had a lot of time for Ken because of things like that’, Sutton says. - Lynn Seymour Remembers Rudolf Nureyev (8:40). Speaking before an audience, the choreographer Lynn Seymour talks about the qualities of Nureyev. The interview is audio only, presented over a still image of Nureyev from Russell’s film. - The Guardian Lecture: Ken Russell in Conversation with Derek Malcolm. Running approximately 90 minutes and presented over the film (in the manner of an audio commentary), this audio recording is from 1987 (the time of the release of Gothic) and sees Russell, speaking before an audience, reflecting on his work as a filmmaker to that point. - Textless Opening and Closing Credits (4:13). Presented mute, this contains the footage from the film’s opening and closing titles sequences sans the credits themselves. - Valentino Stills and Collections Gallery (9:31). Here are stills, promotional materials, magazine spreads and other visual material used to promote the film, accompanied by some of the songs used in the picture. - The Funeral of Valentino (8:44). This contains newsreel footage of Valentino’s funeral, some of which was used in the opening titles sequence of Russell’s film. - the film’s original trailers (4:45). - the film’s original TV spots (2:30).

Overall

Russell’s biopic of Rudolph Valentino displays the director’s characteristic fascination with the caricature, the grotesque and the carnivalesque. ‘Every day is Halloween in this town’, June declares more than once in the film, and her words may very well echo in the ears of the film’s viewer. The picture offers a savage indictment of Hollywood; and though it deviates from what is known about Valentino and the other characters who appear in the film in a number of ways, the film itself is arguably less concerned with the ‘facts’ than with an exploration of how subjective the very concept of ‘truth’ is. Hollywood’s executives are shown to be callous men driven by money, who over Valentino’s corpse argue over how best to exploit his death, and through flashback are shown exploiting the comparatively innocent dancer-actor during his lifetime. It’s a fascinating film – not Russell’s best, but clearly a Ken Russell film. The British Film Institute’s new Blu-ray release of the picture is exemplary, containing a superb presentation of the main feature and some impressive and insightful contextual material, making this a must-buy release for anyone remotely interested in Russell’s films. Russell’s biopic of Rudolph Valentino displays the director’s characteristic fascination with the caricature, the grotesque and the carnivalesque. ‘Every day is Halloween in this town’, June declares more than once in the film, and her words may very well echo in the ears of the film’s viewer. The picture offers a savage indictment of Hollywood; and though it deviates from what is known about Valentino and the other characters who appear in the film in a number of ways, the film itself is arguably less concerned with the ‘facts’ than with an exploration of how subjective the very concept of ‘truth’ is. Hollywood’s executives are shown to be callous men driven by money, who over Valentino’s corpse argue over how best to exploit his death, and through flashback are shown exploiting the comparatively innocent dancer-actor during his lifetime. It’s a fascinating film – not Russell’s best, but clearly a Ken Russell film. The British Film Institute’s new Blu-ray release of the picture is exemplary, containing a superb presentation of the main feature and some impressive and insightful contextual material, making this a must-buy release for anyone remotely interested in Russell’s films.

References Barton, Ruth, 2014: Rex Ingram: Visionary Director of the Silent Scream. University Press of Kentucky Basinger, Jeanine, 1999: Silent Stars. New York: Alfred A Kopf Hansen, Miriam, 1991: ‘Pleasure, Ambivalence and Identification: Valentino and Female Spectatorship’. In: Butler, Jeremy G (ed), 1991: Star Texts: Image and Performance in Film and Television. Wayne State University: 266-98 Harper, Sue & Smith, Justin T, 2012: British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure. Edinburgh University Press Lanza, Joseph, 2007: Phallic Frenzy: Ken Russell and His Films. Chicago Review Press Shail, Robert, 2007: British Film Directors: A Critical Guide. Southern Illinois University Press

|

|||||

|