|

|

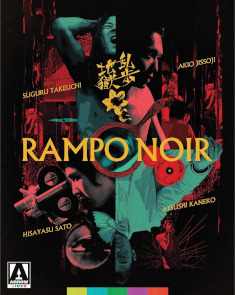

Rampo Noir

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray A - America - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (20th January 2025). |

|

The Film

Edogawa Rampo was a writer of strange tales during the Taishō period (1912-1926), a period between the wars marked by a clash between the traditional and the Western influences in politics and culture. Although Rampo's name is a Japanese transliteration of Edgar Allan Poe, Rampo's weird tales also demonstrated the influence of (or at least the same influences on) the likes of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Gaston Leroux – with more than one locked door mystery for his own recurring detective Kogoro Akechi – as a sort of contemporary to H.P. Lovecraft, contributing to the definition of the era's artistic movement as ero guro nansensu (or "erotic grotesque nonsense"). Rampo continues to be much-adapted in Japanese cinema and is perhaps most familiar indirectly through some of exported adaptations from the pinku eiga/Roman Porno cycles of the late sixties to the eighties like Daiei's Blind Beast, Nikkatsu's Watcher in the Attic (a locked room detective story loosely-adapted a number of times with added erotic elements), Toei's Horrors of Malformed Men, and more recently Shinya Tsukamoto's Gemini (more so, perhaps, than the fantastic, fictionalized reflexive biopic The Mystery of Rampo which made it stateside). Rampo Noir from 2005 is a multi-director anthology from co-producer Kadokawa Eiga made during the second boom of modern J-Horror – Kadokawa having published both the literary sources and produced the adaptations of Ringu and a number of other major turn-of-the-millenium J-Horror titles along with the original1976 theatrical adaptation of The Inugami Family in the seventies along with its 2006 remake by the same director with much of the same cast – as well as being a vehicle for actor Tadanobu Asano (Bright Future) in four tellings by veteran directors Akio Jissoji (The Prosperities of Vice) and Hisayasu Satô (Lolita Vibrator Torture) as well as manga artist Atsushi Kaneko and music video/TV commercial director Suguru Takeuchi. The shortest segment is Takeuchi's "Mars' Canal", a dialogue-less, even near-silent piece in which Asano plays a man so consumed by memories of a lost love he may have murdered that they fuse into one being through a Narcissus-like gaze into a crater full of water on a desolate landscape that may indeed be Mars or one of the film's first externalized inner worlds of the characters. The fusion is a modern dance-type performance in which we make the assumption that Asano's partner is a woman. Both Asano and male dancer Kaiji Moriyama have long hair and lanky musculature, and the combination of light, shadow, motion, and editing to blur the boundaries between the two bodies to the point that we do not know which one collapses before the crater in the final shot. While visually stunning, the segment merely honors the 1927 source story without really embodying it. In Jissolji's "Hell's Mirror", Asano is Rampo's regular detective Akechi who happens to be in the historical village of Kamakura where he wife is being treated at a local sanatorium when he is asked to consult on a series of murders of women whose faces have inexplicably "melted." The presence of a distinctive handmade mirror takes him to a antiques shop run by widow Azusa who reveals that her brother-in-law Toru (Azumi's Hiroki Narimiya) has kept the ancient Kamakura technique of mirror-making alive and regularly presents the traditional style to their shop's patrons. Toru is obsessed with surpassing the technique, and Azusa quietly suspects that he has discovered the secret behind the supposedly mythical "shadow mirror" created for performing black magic. With the exception of some dodgy digital effects, Jissoji's segment is beautifully designed and photographed with mirrors in virtually every shot and almost every angle canted; however, it too relegates the source story's central themes to the background in favor of a more conventional detective story elements incorporaed from other Rampo stories (as elaborated upon in the commentary track). Asano is also Akechi in Sato's "Caterpillar" but only makes bookending appearances with his new assistant (Nobody Knows' Hanae Kan) when he is bequeathed the "art" collection of master thief "Man of Twenty Faces" including a reel of film depicting the creation and acquisition of his first object of beauty. The story proper is about Tokiko (Returner's Yukiko Okamoto), the "good wife" to "war god" First Lieutenant Sunaga (Demonlover's Nao Ômori) who returned from battle seriously wounded. Tokiko alone cares for her burn-scarred, limbless, voiceless husband in her artist father's seaside mansion that the recluse abandoned for a nearby island, having banished every mirrored surface from the house to protect her husband from seeing himself. She resists the lustful overtures of her father's pining assistant Tarô Hirai (Taboo's Ryûhei Matsuda) - named after Rampo's birth name – who spies on Tokiko whose care for her husband has taken on sadomasochistic dimensions that have Tarô questioning the degree to which Tokiko is her father's daughter. Although Sato's telling of the Rampo source story takes some liberties – see the commentary track discussion below – it is perhaps most faithful in addressing the once-banned source story's themes of not exactly body horror but bodily transformation from mutilation to the fantasy of metamorphosis, devotion and sadomasochism, focusing particularly on the emotions of the "good wife" with the inserted Tarô a "watcher in the attic" voyeur whose observations expand the viewer's understanding of the story without taking over as narrator (the viewer will have already arrived at certain conclusions before he speaks them). While the Takeuchi and Jissoji episodes only suggested some of their more grisly elements and the Kaneko's final story puts everything on display, Sato strikes the right balance between the uncomfortable imagery he shows and the feelings and off-screen actions they inspire. While the viewer might have hoped that the film would explore some of the backstory including Tokiko's father and his artistic creations which may or may not have involved his surgical training that he passed on to his daughter, which also would have shed light upon what Tarô considers merely beautiful and true art. Whereas Jissoji's and Kaneko's stories are most ornately-designed in terms of decoration, costumes, and photography, and Takeuchi apart from the Mars landscape all but shut out any sense of environment with darkness, Sato gives the impression of creating his world out of found locations and objects including the wardrobe with windows and broken mirrors seeming to artistically scatter available light into his minimalist settings. All of these approaches suit the exploration of characters' inner worlds and the intrusions of both memory and reality. Kaneko's "Crawling Bugs" is not a "when insects attack" film but the story of Masaki (Asano) who is so repulsed by contact with the physical world and believes it in turn has rejected him as he breaks out into rashes that a physician (Sky High's Hiromasa Taguchi) – his only and not-exactly-willing confidante – believes is more psychological than dermatological. In spite of this pathological repulsion, Masaki is in love with actress/singer Fuyu Kinoshita (Samurai Fiction's Tamaki Ogawa). As he stalks her and watches her encounters with rich suitors – including one with a blood fetish involving leeches – Masaki grows more and more frustrated that he cannot touch her. When he accidentally strangles her to death, Masaki lights upon how he can worship her without touch; however, when the natural cycles of decay make themselves known on the surface, Masaki goes to increasingly desperate lengths to preserve her shell. Floridly-designed with eye-popping colors and anachronistic detail that seem to bounce back and forth between the Taishō era and grimmer modern world – the former expressed with obvious back projection and painted backdrops and the latter through the spinning of a washing machine and urban pornographic window displays – "Crawling Bugs" perhaps gives Asano the most opportunity to demonstrate his range, and it may be the most relatable to Western audiences in terms of stories told from the killer's increasingly unreliable point-of-view; and the latter might be why it feels like the least interesting installment. The final shot of the film has a cheeky tone that suggests that Kaneko was uninterested in actually engaging with the obsessive elements beyond the surface of manga-like panels (especially when combined with a smash cut to anthology's overall end credits to a tonally-clashing pop music track in the tradition of other J-Horror films with completely-unrelated tie-in singles). While Rampo continues to be adapted in Japanese film and television – along with theatre, manga, and video games – Rampo Noir has thus far been the last we have heard from him in the West apart from "The Edogawa Rampo Reader" compendium of new translations of stories and essays and Barbet Schroeder's French/Japanese Inju: The Beast in the Shadow which has only gotten as far West as French-speaking Canada. Hopefully, we will not only see more Japanese cinematic imports of Rampo adaptations but a wider availability of his written work this millennium.

Video

Unreleased theatrically in the U.S. or the U.K., Rampo Noir was first accessible as a Hong Kong DVD with English subtitles and then as a Region 1 DVD from Genius Products. We have no information on the transfer other than it being a "High Definition Blu-ray™ (1080p) presentation" and the combination of film capture and some digital effects might mean that the source is the original HD master struck upon release. The film has a variable texture with "Mars' Canal", "Caterpillar", and "Crawling Bugs" looking "filmic" while "Mirror Hell" has sort of a digital video look which may have something to do with the use of on-camera filters, digital effects, and overexposed light bounced off of several mirrored surfaces with the sets back towards the camera giving a hazy sense to some master shots. "Caterpillar" also contains some overexposed and digitally-solarised shots. Fine detail is evident in close-ups – uncomfortably so when it comes to Sanaga's bleached burn make-up – across all the films but Asano, Narimiya, Matsuda, and the female performers are generally given the glamour treatment. A few cutaway shots during the first story have a certain video-like fuzz and jaggedness that may be an artistic choice.

Audio

The sole audio option is an excellent Japanese LPCM 2.0 stereo track that clearly delivers dialogue, voice-over, and the varied sound design from the first story's near total silence to the shattered glass and sizzling flesh of the second story, to the razor swipes and bone-sawing of the third, and the auditory insect infestations of the final tale. The optional English subtitles are free of errors. Presumably there is some legal or studio-stipulated reason for the translations of some of the titles as the published title "The Martian Canals" sounds less awkward than "Mars's Canal" or "Hell of Mirrors" over "Mirror Hell".

Extras

Extras commence with a highly informative audio commentary by Japanese film experts Jasper Sharp and Alexander Zahlten. The discuss Takeuchi's work in art installations and provide background on the source story which was only recently translated into English as part of the "Edogawa Rampo Reader." For "Mirror Hell" they provide background on the Jissoji, how the Buddhist themes of his feature films had already been evident in his kids series – the style of which was heavily influential on how such series were made including the various "Mighty Morphing Power Rangers" franchises – and Jissoji's prior Rampo adaptations, as well as the presence in the cast of actress/director Yumi Yoshiyuki who had previously appeared in Jissoji's Rampo film The Murder on D Street. The pair discuss the "Mirror Hell" source story – and recurring themes throughout Rampo's works of voyeurism, optical devices, and early cinematic innovations like references to attending stereoscopic films in 1920s Japan – and reveal that it does indeed incorporate material from the Rampo detective story "The Mysterious Crimes of Dr. Mera" while also noting that Japanese society is so familiar with Rampo's works that domestic audiences would recognize the references and borrowings. Of "Caterpillar" they provide some needed background on Sato who is one of the four major pink film figures of the eighties and his own recurring fixation on eyes, voyeurism, and eye violence (as well as providing the distinction between pink and Roman Porno films that will be familiar to fans but necessary across different films and releases from other labels). They also reveal that pink film pioneer Kôji Wakamatsu (Ecstasy of the Angels) was so incensed that Sato downplayed the story's anti-war themes and changed the ending that he mounted his own feature-length adaptation in 2010 to good reception. Neither commentator has read the source story for "Crawling Bugs" so they go back and forth between commening on the episode and its production and Rampo in popular culture – many of these grisly tales were serialized in boys' magazines before Chinese censorship tamped down in the thirties but are usually discovered by fans as children – and the concept of ero guro nansensu. They also discuss the film's reception by some as too "arty" and the possible intentions of producer Dai Miyazaki (Shock Labyrinth 3D). "Another World" (14:04) is an interview with "Mars's Canal" director Takeuchi who discusses his work in music video and TV commercials and the offer to do the Rampo tale, the necessity of the changes he made in adaptation, scouting the locations in Iceland, and working as his own cinematographer. "A Moving Transformation" (25:07) is an interview with "Caterpillar" director Sato who had previously worked with producer Miyazaki on three V-cinema productions and that Miyazaki chose him to do "Cateprillar" because he had already developed a cost-prohibitive feature-length adaptation script. He also discusses scouting the location which was a hotel development that was abandoned when funding collapsed as well as the contributions of his cinematographer Akiko Ashizawa (Loft) who worked out optical effects in-camera and utilized high-contrast film stock and skewed the grading. He briefly discusses the varied responses to his adaptation without mentioning Wakamatsu who reportedly heckled him during the screening according to the commentary. "Butterfly Queen" (13:49) is an interview with "Crawling Bugs" director Kaneko who reveals that in adapting the story he only kept the actress and the driver but threw everything else out in order to preserve the story's essence within the limitations of budget and running time. He focuses on the development of the color scheme in the sets, wardrobe, and grading – with an emphasis on red not for blood but for the cotton rose flower – and also discusses the color schemes of the other stories. He also discusses working with Asano and suggests that the film's appeal came out of his relative inexperience (Kaneko did go to film school but chose to go into writing and illustrating manga before being offered the film). "Hall of Mirrors" (25:19) is an interview with "Mirror Hell" cinematography advisor Masao Nakabori who got into effects photography at Tsubaraya Productions where he eventually worked with Jissoji on several kids shows. He and his team were so devoted to Jissoji that they wanted to do a feature film with him. Nakabori would be operator on This Transient Life and Mandala before graduating to cinematographer on Poem and It Was a Faint Dream. He goes into some depth about working with Jissoji in television drama at TBS – noting that Jissoji's works were the only ones in that medium at the studio that had been preserved on film via kinescope – and explains why he had to promote one of his operators to shoot "Mirror Hell" due to a scheduling conflict as well as his feelings that he would have done it differently due to the way he and Jissoji worked together. "The Butterfly Effect" (15:47) is an interview with "Caterpillar" cinematographer Ashizawa who recalls finding a job at pink company Watanabe Productions while in school and not being intimidated, spending a few years as an assistant director before becoming interested in the camera and apprenticing under a cinematographer. She discusses her work with Sato, the strong content, his themes of eyes and the relationship between the watcher and the watched, as well as the location shoot for the Rampo story. "Looking in the Mirror" (13:58) is a new interview with "Mirror Hell" actress Yoshiyuki who had already worked with Jissoji on a Rampo adapatation (see above) and started to familiarize herself with the works of both writer and director. Although she does not have much screen time, she is able to provide some details of the shoot, including the use of mirrors on all of the sets, as well as details about her scenes, noting that not only did she not know anything about the tea ceremony other than what she was instructed to do on the set – she also notes very few people in Japan actually do know how to perform the ceremony – her flashback sex scene, and her make-up and the wig that went flying off during one take of her throwing her head back in ecstasy. The disc also includes the stage greeting with the cast and directors from the Japanese premiere(15:06) as well as the feature-length documentary "Crossing the Lens" (75:45) by Tatsuya Fukushima who discusses his approach to documentary filmmaking and structures the piece by short and each interview by recurring questions; as such, the interviews themselves are less interesting than all of the behind the scenes footage of the Iceland shoot, the "Caterpillar" shoot which reveals a jovial set despite the subject matter as well as what some of the scenes look like without the film grading, the challenges of shooting on the mirror sets for "Mirror Hell", and a look at the deliberately artificial "Crawling Bugs" sets. While there is some overlap with the new interviews, we do get brief interviews with various cast members, producer Miyazaki, and some lengthy comments from the late Jissoji which prove interesting. The disc closes with image galleries for each of the stories.

Packaging

The disc case comes in a slipcover with a reversible sleeve featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Luke Insect, and an illustrated collector's booklet featuring new writing on the film by Eugene Thacker and Seth Jacobowitz (none of which were supplied for review).

Overall

While Rampo continues to be adapted in Japanese film and television, Rampo Noir has thus far been the last we have heard from him in the West. Hopefully, we will not only see more Japanese cinematic imports of Rampo adaptations but a wider availability of his written work this millennium.

|

|||||

|